Abstract

We present a novel approach to understand what women want when they go to a high-end store to buy beauty products. We embed a survey into an experiment, presenting systematically varied vignettes about shopping for beauty products. Different messages are combined in a systematic way, with the respondent required to assign a rating to the entire combination. A deconstruction of the responses to the contribution of elements reveals different points of view held by those who respond. These four segments are Focus on self-confidence; Focus on the product/expert; Focus on the experience; and Focus on nothing specific. These four mind-sets can be identified by a short interaction with the salesperson, or with a computer tablet, smartphone, and appropriate, sales-driving message given to the shopper.

Introduction

During the past two or three decades a swell of interest in the shopping experienced has swept over the world of consumer package goods. Whereas in the 1960’s to 1980’s it sufficed to know what consumers liked and wanted to hear, and what packages would appeal to them, attention in the late 1980’s and onwards has turned to the experience of shopping. By experience we do not mean just the perception of packages on the shelf, but rather on the experience, such as the interaction of the shopper with the store, and with the people who work there.

Our focus here is the experience of the department store, and specifically the make-up counter found in high end department stores where specialists, individuals paid by the cosmetics manufacturers, sell their expensive make-up products to women shoppers. One need simply visit any high-end department store around the world to see these make up professionals competing for the shopper’s attention, often gifts, expertise, or just an easy way to purchase.

The question motivating this research was quite simple. It was ‘just what does it take to make a shopper interested in purchasing from a specific vendor, with a stand at the store?’ In more concrete terms, what does the shopper want, and what specifically must one say to the shopper to drive purchase at the vendor’s stand.

The approach is this study is motivated by the emerging science of Mind Genomics, focusing on the relation between messaging given to consumers/customers, and choice. The objective of Mind Genomics is to uncover the persona of an individual for a given experience, such as shopping for cosmetics. Often the unspoken hope is that somehow by minding terabytes of purchase data, one might figure out exactly what to say to a specific individual about a specific product. The result is an explosion of methods using pattern recognition and artificial but rarely the simple prescription of what exactly to say to a specific person who presents herself at the cosmetic counter and will only 30 seconds of her time before moving on.

By uncovering the mind-set of a shopper at the time of shopping in the store, the salesperson or company representative can use the proper language to drive interest and a sale. In a sense, Mind Genomics identifies the mind-set of a shopper for a topic, and prescribes what to say, following the way an experienced salesperson ‘sizes up’ a customer and knows what are the word which might sway the customer.

Mind Genomics is based upon the approach in mathematical known as Conjoint Measurement [1,2] and Information Integration Theory [3]. Many of the traditional uses have been methodological in nature, showing the power and application of new variations of the technique. It is only in the past three decades that conjoint measurement, in the form of Mind Genomics has been used to create banks of knowledge, rather than one-off exercises in method. Mind Genomics has been used for more than three decades in the consumer products world [4–6], as well as finding use in the world of health to communicate the right messages with patients [7], along with efforts in car sales and insurance sales (unpublished data from author HRM.) The application of Mind Genomics is thus appropriate.

The objective of this study is to determine whether a woman accustomed to shopping in a high-end store for cosmetics could be understood in terms of the messages to which she respondents, and whether, in fact, is there more than just one mind-set for shoppers. Discovering a shopper’s mind-set in almost an instantaneous way (15–30 seconds) might well help to increase the sales. Furthermore, the interaction would go a long way towards removing the fear of being ‘followed’ on the web through cookies, and having intrusive advertising pushed as one traverses the internet, either for shopping or for information.

In today’s world, where information is overflowing, there is no dearth of information about a person. There is, however, a massive lack of actionable data for specific situations encountered every day. Moreover, there is an absence of methods which quickly ‘understand’ the mind of a consumer in virtually any area, methods based on experimentation. Mind Genomics provides one way to generate that data. The ingoing premise of Mind Genomics is that for virtually any situation that can be dimensionalized, one can uncover the relevant personas or mind-sets which co-exist in a population of consumers, mind-sets. One needs to do small experiments to uncover these mind-sets. These mind-sets cannot easily, readily, quickly and inexpensively be uncovered simply by KNOWING WHO A PERSON IS. That is, KNOWING WHAT A PERSON THINKS is different, and often elusive, not easily captured by today’s technologies such as Big Data. The research, in spirit, is based in part on the breakthrough ideas of Nobelist Daniel Kahneman, who talked about the two modes of thinking, the rational thought, System 2, and the more typical mode in shopping, System 1, where impulse leads [8].

Method

Mind Genomics begins by identifying the topic, then asking a set of questions, and for each question providing a set of six answers. For this case of Mind Genomics, we proceed with the creation of six questions, each of which is given six answers. The questions and answers are shown in Table 1. There are no fixed questions and answer, but there is the stipulation that the questions should ‘tell a story,’ in the same way that a reporter uses the ‘what, how, where, why, and who’ to tell a story. The questions are never shown to the respondents, but only used to develop answers. It is the answers or really the systematic combination of answers that are shown to the respondent.

Table 1. The questions (silos) and answers (elements) for the cosmetic shopper study.

|

Question A: Why do you shop for cosmetics? |

|

|

A1 |

I want perfect skin |

|

A2 |

I have combination skin |

|

A3 |

My skin is needy |

|

A4 |

My skin is unpredictable, always changing |

|

A5 |

For me it’s about staying sexy |

|

Question B: What do you do, or want to achieve, when you put on cosmetics? |

|

|

B1 |

I always put make-up on before I go out |

|

B2 |

I always want to look like ME, not a made-up version of me |

|

B3 |

I totally believe in inner beauty! |

|

B4 |

I believe my face and body are a medium for self-expression |

|

B5 |

I need a make-up that taps into my flirty and sensual side |

|

Question C: How do you want to look, or feel when you put on makeup? |

|

|

C1 |

I like a glamorous make-up look |

|

C2 |

My style can be described as conservative |

|

C3 |

At the beauty counter, at first, I’m usually a little bit shy and stay to myself |

|

C4 |

At the beauty counter, I can appear rushed, mistrusting, non-committal |

|

C5 |

My style… revealing, sexy, with bare, nude, natural make-up |

|

Question D: How do feel about new products that you see in the store? |

|

|

D1 |

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

|

D2 |

When buying a new skincare product… I find it hard to trust the skin-care consultants |

|

D3 |

At times I feel too nervous to ask questions from beauty consultants |

|

D4 |

I can feel bored and lose interest quickly… unless some product captures my imagination |

|

D5 |

I’m a more visual shopper… I love touching, smelling and seeing all the products |

|

Question E: How do you feel when you shop and have a beauty consultant at the store? |

|

|

E1 |

My challenge is finding the perfect skincare product |

|

E2 |

I ask a lot of questions to get all the product details… even though I’ve done my own research |

|

E3 |

I want the beauty consultant to hold my hand, and show me exactly how to use the products |

|

E4 |

I am someone who loves to customize make-up in her own unique way |

|

E5 |

I like brightness, colors, fragrance, soft music; variety… I only go into beauty stores that exude those qualities |

|

Question F: What would you like beauty consultant to know about you so that she can help? |

|

|

F1 |

I need the beauty consultant to show me the ultimate, top of the line skin-care range… everything else is a waste of my time |

|

F2 |

I want the beauty consultant to use an educational approach, using facts, to support their claims |

|

F3 |

I want a “Go To” consultant who knows me intuitively, and can make my experience more personal each time I return |

|

F4 |

In an ideal world I’d be left completely alone to look at, touch and try things, before I am helped |

|

F5 |

When I am purchasing makeup, skincare products or fragrances, I like the staff to be playful, spontaneous and funny |

|

Question G: Describe your ultimate skincare shopping experience in one word |

|

|

G1 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is pleasurable |

|

G2 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is informative |

|

G3 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is glamorizing |

|

G4 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is therapeutic |

|

G5 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is transformative |

As Table 1 shows, the questions and answers do not rigidly fit into a framework. The real reason for the format is ‘bookkeeping.’ When two answers or elements are put into the same silo or answer the same question, they never will appear together in a vignette. The bookkeeping system is totally transparent to the analysis, which ends up looking at the 35 answers or elements as completely independent ideas.

Mind Genomics combines the answers in Table 1 into short, easy-to-read vignettes, using an experimental design [9,10]. The experimental design stipulates the specific combinations to be tested. Each respondent evaluated 63 unique combinations, the vignettes. The design is structured as follows:

- Each question contributes an answer from its five answers 30 times in the 63 vignettes, and absent from 33 vignettes.

- Each answer appears 6 times in the 63 vignettes, and absent from 57 vignettes.

- The vignettes are of unequal sizes. The underlying experimental design calls for 31 vignettes comprising four answers, 22 vignettes three answers, and 10 vignettes comprising two answers.

- Each respondent evaluated a unique set of combinations. That is, the experimental design was fixed mathematically, ensuring that all 35 answers or elements were statistically independent of each other. However, each of the 251 respondents evaluated a unique set of 63 vignettes, enabling the experimental design to cover a great deal of the so-called design space of possible combinations.

Running the Study

The 251 respondents who participated were selected to be beauty product shoppers. The study used a commercial e-panel provider, specializing in these types of on-line studies. The respondents had already signed up to participate in various studies and were incentivized by the panel company. No one from the researcher group ‘knew’ the identity of the panelists, who could only be identified by their answers, and by an extensive, self-profiling questionnaire administered AFTER the evaluation of the 63 test vignettes.

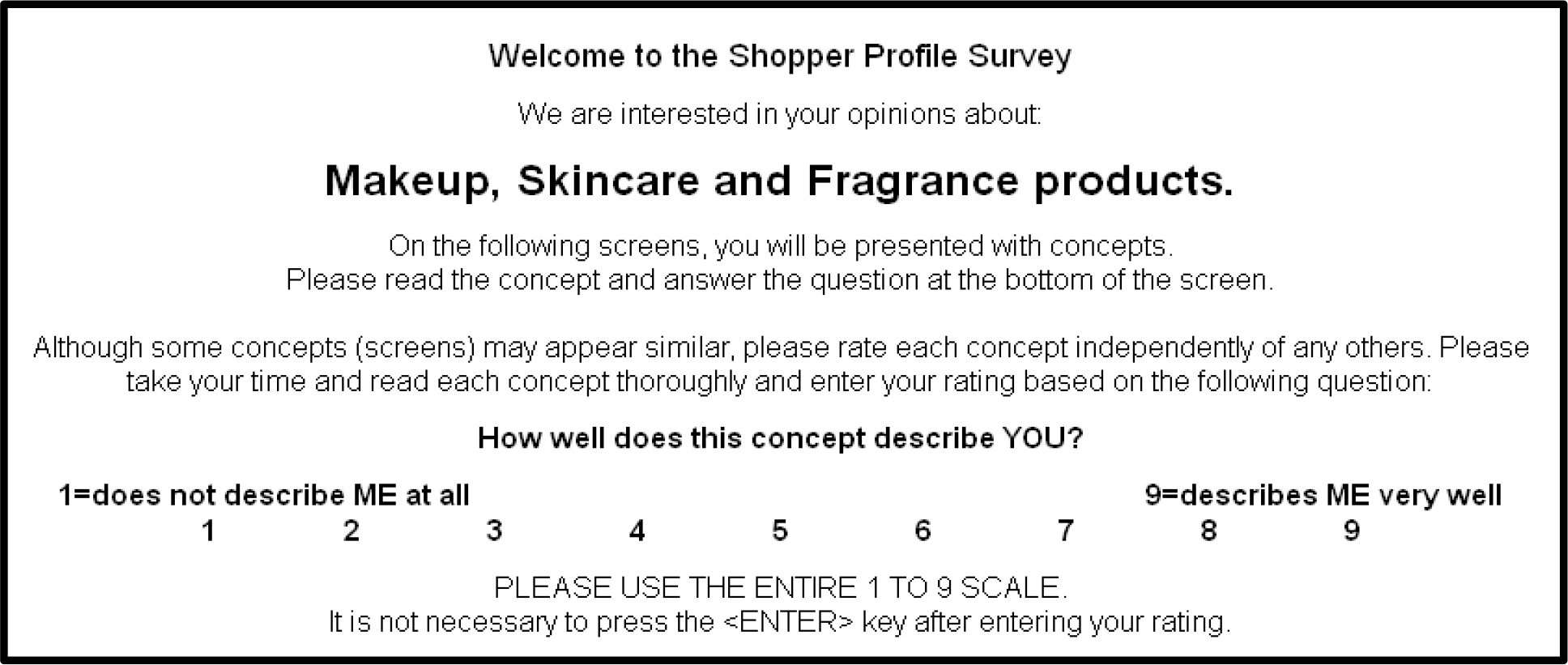

Figure 1 shows the orientation page. The page provides very little data about the purpose of the study, and the nature of the test stimuli. The reason for the paucity of information is that we want the respondent to be free of any expectations, so that the answers reflect her attitudes alone. The only information of any relevance beyond the topic is the fact that the orientation page reinforces the fact that all vignettes differed from each other. Although this might seem a bit excessive, the reality of the Mind Genomics studies is that the same elements repeat in different vignettes. Some respondents are upset, feeling that they have ‘already evaluated that vignette.’ The orientation page dispels that worry.

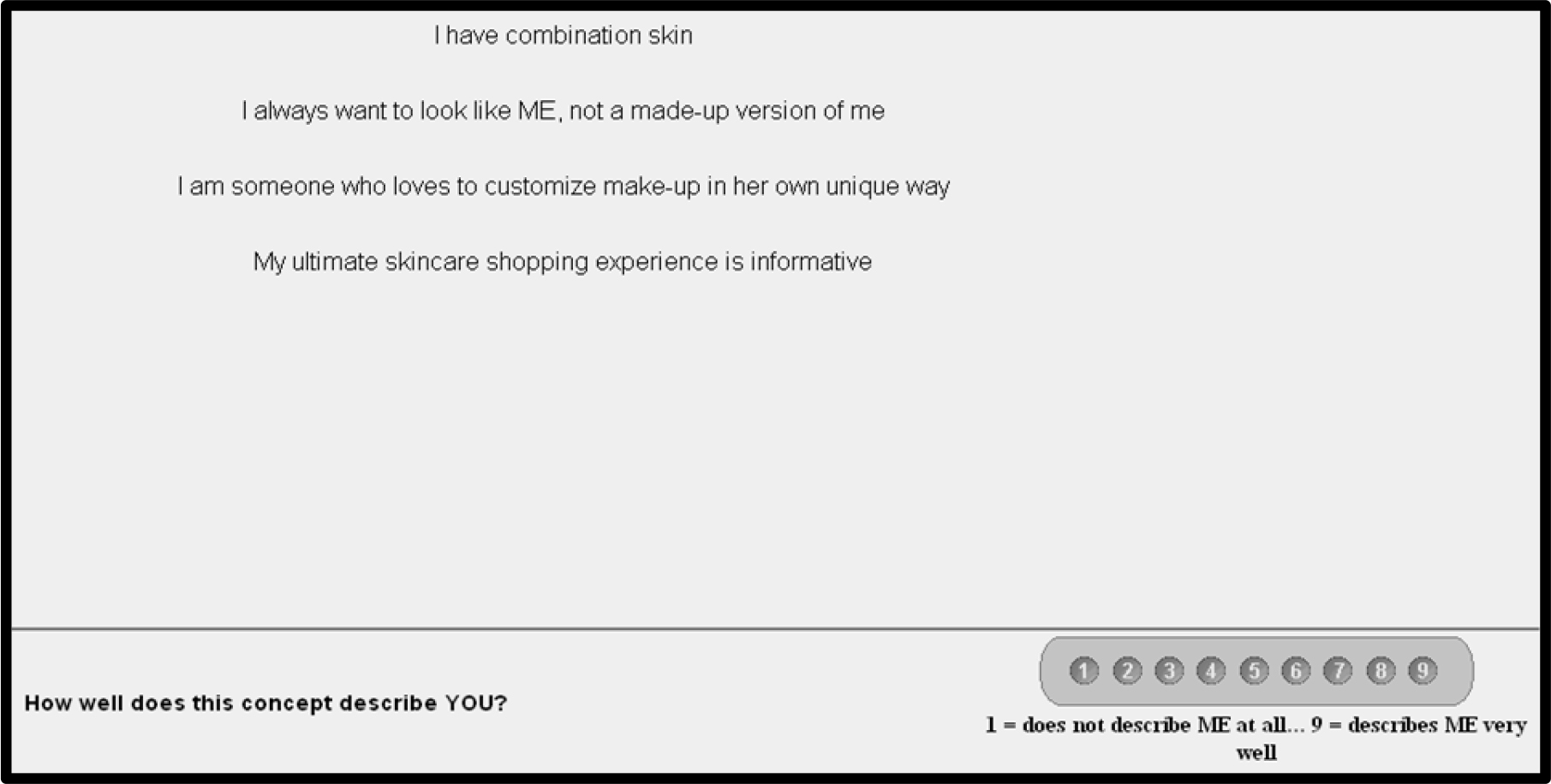

Figure 2 presents an example of a four-element vignette. No effort is made to connect the rows of text. The objective is not to present a densely worded paragraph containing all the information, but rather to throw the different ideas at the respondent, and let the respondent evaluate the combination. The respondent often does so in an intuitive manner, rather than in a considered, intellectual manner, precisely in the manner desired. The objective of Mind Genomics is to pierce the intellectual veneer and move to the emotionally-driven aspects.

Quite often respondents complain that they feel they are doing this task in a random fashion, and that they are not able to give their full attention to the task. They feel that somehow their answers are random.

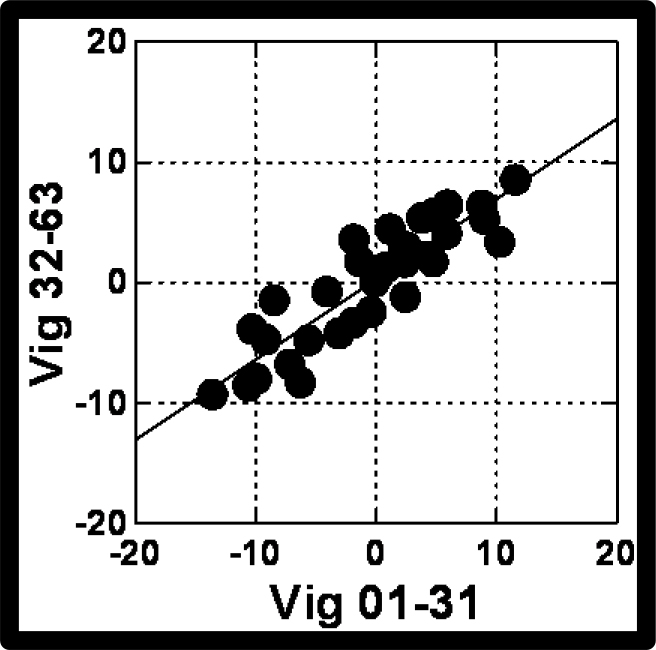

In order to test the robustness of our data, we divided the data set into two halves, the data from the first 31 vignettes, and the data from the second 32 vignettes. We ran the regression analyses twice, one for each data set. Figure 3 shows that the pattern of coefficients (scores, see below for expectation), obtained by analysis of responses to the first 31 vignettes is virtually identical to the pattern of responses to the second 32 vignettes. Furthermore, the coefficients for the 35 elements or answers differ from each other. In other words, the respondents differentiate among the different answers or elements, doing so in a repeatable manner. Thus, the complaint that ‘it’s impossible to keep track’ may be valid for the respondent who wants to be intellectually consistent in assigning the ratings, but it seems to make little difference. Respondents accurately differentiated among the elements, doing so in a reliable fashion, despite what they ‘say’ or ‘complain.’

Figure 1. The orientation page for the beauty shopper experiment.

Figure 2. An example of a four-element vignette.

Figure 3. Scattergram showing the 35 coefficients estimates from the ratings of vignettes 01 to 31, and from vignettes 32 to 63. The two sets of coefficients are very strongly related to each other, suggesting discrimination across coefficients, and reliability across the first and second halves of the experiment.

What Describes the Cosmetic Shopper?

With 251 respondents participating, each seeing a set of 63 different vignettes, we create a single equation showing how each of the 35 elements, the answers to the questions, ‘drives’ the response. The analysis proceeds first by transforming the ratings, so that ratings of 1–6 are recoded to 0, and ratings of 7–9 are recoded to 100. To each recoded value we add a small random number (<10–5.) The rationale is that, when we deal with individual respondent data in segmentation and clustering, we want to ensure that across the set of 63 ratings for a given respondent there is a minimal level of variation in the response. Otherwise, for situations where the respondent rates all vignettes between 1 and 6, or rates all vignettes between 7 and 9, respectively, the transformed ratings would be all 0 or 100, respectively, causing the regression analysis to fail.

We use the method of OLS (Ordinary Least-Squares) regression, to relate the presence/absence of the 35 elements or answers to the binary, transformed rating. OLS regression deconstructs the rating into the contribution of each component (answer, element) as well as estimates the likely response for the zero condition, i.e., a vignette with no elements.

Table 2 shows the deconstruction of the vignettes into the contributions of the individual elements. The deconstruction is made on the full set of 251 (respondents) x 63 (vignettes per respondent), or 15,813 observations.

Table 2. Performance of the 35 elements for the beauty shopping experience. The dependent variable is ‘fits me,’ with 0 = does not fit me, or fits modestly, 100 = fits me)

|

Beauty Shopper – Total Panel – ‘Describes ME’ |

Coeff |

t |

p-Value |

|

|

Additive Constant |

48 |

26.48 |

0.00 |

|

|

D1 |

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

10 |

7.13 |

0.00 |

|

B2 |

I always want to look like ME, not a made-up version of me |

8 |

5.54 |

0.00 |

|

A1 |

I want perfect skin |

7 |

5.18 |

0.00 |

|

D5 |

I’m a more visual shopper… I love touching, smelling and seeing all the products |

7 |

4.95 |

0.00 |

|

B3 |

I totally believe in inner beauty! |

6 |

4.36 |

0.00 |

|

E1 |

My challenge is finding the perfect skincare product |

5 |

3.45 |

0.00 |

|

G1 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is pleasurable |

5 |

3.69 |

0.00 |

|

B4 |

I believe my face and body are a medium for self-expression |

4 |

3.13 |

0.00 |

|

B1 |

I always put make-up on before I go out |

3 |

2.30 |

0.02 |

|

B5 |

I need a make-up that taps into my flirty and sensual side |

3 |

1.98 |

0.05 |

|

E2 |

I ask a lot of questions to get all the product details… even though I’ve done my own research |

3 |

1.86 |

0.06 |

|

E4 |

I am someone who loves to customize make-up in her own unique way |

3 |

1.85 |

0.06 |

|

F2 |

I want the beauty consultant to use an educational approach, using facts, to support their claims |

3 |

2.34 |

0.02 |

|

G2 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is informative |

2 |

1.36 |

0.17 |

|

A2 |

I have combination skin |

1 |

0.36 |

0.72 |

|

C5 |

My style… revealing, sexy, with bare, nude, natural make-up |

1 |

0.58 |

0.57 |

|

F3 |

I want a “Go To” consultant who knows me intuitively, and can make my experience more personal each time I return |

1 |

0.88 |

0.38 |

|

F5 |

When I am purchasing makeup, skincare products or fragrances, I like the staff to be playful, spontaneous and funny |

1 |

0.74 |

0.46 |

|

E5 |

I like brightness, colors, fragrance, soft music; variety… I only go into beauty stores that exude those qualities |

0 |

0.11 |

0.92 |

|

G4 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is therapeutic |

0 |

0.13 |

0.90 |

|

F4 |

In an ideal world I’d be left completely alone to look at, touch and try things, before I am helped |

-1 |

-0.44 |

0.66 |

|

G5 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is transformative |

-1 |

-0.98 |

0.33 |

|

E3 |

I want the beauty consultant to hold my hand, and show me exactly how to use the products |

-2 |

-1.62 |

0.11 |

|

A5 |

For me it’s about staying sexy |

-3 |

-1.87 |

0.06 |

|

G3 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is glamorizing |

-4 |

-2.65 |

0.01 |

|

C1 |

I like a glamorous make-up look |

-5 |

-3.54 |

0.00 |

|

C3 |

At the beauty counter, at first I’m usually a little bit shy and stay to myself |

-5 |

-3.57 |

0.00 |

|

A3 |

My skin is needy |

-7 |

-5.05 |

0.00 |

|

A4 |

My skin is unpredictable, always changing |

-7 |

-4.89 |

0.00 |

|

C2 |

My style can be described as conservative |

-7 |

-4.81 |

0.00 |

|

D4 |

I can feel bored and lose interest quickly… unless some product captures my imagination |

-7 |

-4.89 |

0.00 |

|

D2 |

When buying a new skincare product… I find it hard to trust the skin-care consultants |

-9 |

-6.39 |

0.00 |

|

D3 |

At times I feel too nervous to ask questions from beauty consultants |

-10 |

-6.83 |

0.00 |

|

C4 |

At the beauty counter, I can appear rushed, mistrusting, non-committal |

-12 |

-8.31 |

0.00 |

|

F1 |

I need the beauty consultant to show me the ultimate, top of the line skin-care range… everything else is a waste of my time |

-12 |

-8.22 |

0.00 |

- The additive constant tells us the proportion or conditional probability of a woman saying that the vignette describes her, even without vignette having any elements. Of course, all vignettes had elements, as prescribed by the underlying experimental design. The additive constant should thus be considered as a baseline. Our additive constant in 48, meaning that we begin with half of the respondent say ‘it describes me;’

- We look for high scoring elements. Previous studies suggest that elements with coefficients above 7–8 are meaningful. By meaningful we do not mean statistically significant in the sense of inferential statistics. Rather, by meaningful we mean that the message covaries with relevant external behaviors.

- The four strong performing elements appear to tap a variety of wants and descriptions, ranging from confidence (I like products that make me feel confident about myself), to performance (I want perfect skin) to experience (I’m a more visual shopper … I love touching, smelling, and seeing all the products.’)

- Surprisingly, the respondents do not feel any warmth towards the beauty consultants, and indeed even feel nervous. These are the elements with high negatives, suggesting that they do not describe the respondent. They suggest warning flags for the beauty counter, and company employing such beauty consultants.

When buying a new skincare product… I find it hard to trust the skin-care consultants

At times I feel too nervous to ask questions from beauty consultants

At the beauty counter, I can appear rushed, mistrusting, non-committal

I need the beauty consultant to show me the ultimate, top of the line skin-care range… everything else is a waste of my time

- The t statistic and the probability values suggest that coefficients beyond +/- 3 are ‘statistically significant.’ They are significant because of the large base size. As noted above, we should focus on elements with a coefficient of +7 or higher as meaningful.

Comparing the strongest elements which drive ‘similar to me’ and which drive ‘different from me’

We can turn our scale around, focusing on the votes of respondents who rated the vignette as being ‘different from me.’ That is, we can recode the scale as 1–3 (most different) as ‘100’, and 4–9 (less different) as ‘0’. The analytic exercise may seem tautologous, but we want to make sure that we are not dealing with a few positive elements, with the remaining elements settling somewhere in the middle. We may or may not be looking at two types of elements. Table 3 suggests, however, that at least for the total panel, the scale is truly unipolar. Furthermore, and most important from a substantive point of view is the feeling that the interaction with a beauty consultant simply does not describe them.

Table 3. Comparison of elements which are strongest when the scale is looked at from the top down ‘similar to me’ versus when the scale is looked from the bottom up, ‘different from me.’ The results suggest that for the total panel, the scale describes a single continuum, similar to different.

|

|

|

Similar Top 3 |

Different Bottom 3 |

|

Additive constant |

48 |

19 |

|

|

Elements which drive ‘similar to me’ |

|||

|

D1 |

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

10 |

-6 |

|

B2 |

I always want to look like ME, not a made-up version of me |

8 |

-5 |

|

A1 |

I want perfect skin |

7 |

-4 |

|

D5 |

I’m a more visual shopper… I love touching, smelling and seeing all the products |

7 |

-5 |

|

B3 |

I totally believe in inner beauty! |

6 |

-5 |

|

G1 |

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is pleasurable |

5 |

-4 |

|

E1 |

My challenge is finding the perfect skincare product |

5 |

-3 |

|

Element which drive ‘different from me’ |

|||

|

D2 |

When buying a new skincare product… I find it hard to trust the skin-care consultants |

-9 |

5 |

|

D3 |

At times I feel too nervous to ask questions from beauty consultants |

-10 |

8 |

|

F1 |

I need the beauty consultant to show me the ultimate, top of the line skin-care range… everything else is a waste of my time |

-12 |

9 |

|

C4 |

At the beauty counter, I can appear rushed, mistrusting, non-committal |

-12 |

8 |

What do you say to support a reason for beauty shopping?

When we talk about a reason for shopping, say ‘information,’ are there any elements or answers which become extremely important? We have control over the messaging and decide to look at those messages which synergize with the message ‘My ultimate skincare shopping experience is informative.’ Conversely, when we talk about shopping for pleasure, ‘My ultimate skincare shopping experience is pleasurable’ are the same elements important as we saw when we talked about shopping for information? In other words, are there synergisms between elements, so that we can produce more powerful communications to attract the shopper?

We can answer this question by sorting our data into seven strata. Each stratum is defined by holding constant one of the reasons in the stratum. That is, we can sort our data into all those vignettes which have ‘I shop for pleasure.’ Every other silo and element, question and answer, varies except the reason, which is ‘My ultimate skincare shopping experience is pleasurable.’ All the vignettes analyzed have this one reason, one element, in common.

When we do this sorting, and then run our OLS regression on all elements as predictors, EXCEPT elements for question G, the reason, which is constant in the vignette, we find some remarkable synergisms.

- Some elements perform spectacularly when paired with one description of the ultimate shopping experience yet perform poorly when paired with another description. Consider these two elements, which synergize dramatically with the element ‘My ultimate skin care shopping experience is therapeutic.’ They have coefficients of 22 and 20, respectively, for the total panel.

I always want to look like ME, not a made-up version of me

I like products that make me feel confident about myself

These elements may either score moderately well, or be irrelevant, when paired with another description. They certainly do not score the 22 and 20 that they do when paired with the ultimate experience being therapeutic.

- The foregoing approach is called scenario analysis. The data are sorted into strata, based upon the different elements in one silo or question.

- We see the strongest performing synergisms in Table 4. An element or answer can perform moderately, unless paired with an element with which it synergizes.

Table 4. Strongest performing elements for the total panel when the description of the ultimate skincare shopping experience is defined in different ways.

|

. |

Pleasure: My ultimate skincare shopping experience is pleasurable |

|

|

B3 |

I totally believe in inner beauty! |

7 |

|

E4 |

I am someone who loves to customize make-up in her own unique way |

7 |

|

Informational: My ultimate skincare shopping experience is informative |

||

|

B4 |

I believe my face and body are a medium for self-expression |

14 |

|

D1 |

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

12 |

|

B2 |

I always want to look like ME, not a made-up version of me |

11 |

|

None |

||

|

D1 |

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

10 |

|

Therapeutic: My ultimate skincare shopping experience is therapeutic |

||

|

B2 |

I always want to look like ME, not a made-up version of me |

22 |

|

D1 |

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

20 |

|

F5 |

When I am purchasing makeup, skincare products or fragrances, I like the staff to be playful, spontaneous and funny |

12 |

|

B3 |

I totally believe in inner beauty! |

11 |

|

B4 |

I believe my face and body are a medium for self-expression |

10 |

|

F2 |

I want the beauty consultant to use an educational approach, using facts, to support their claims |

10 |

|

A1 |

I want perfect skin |

8 |

|

Transformative: My ultimate skincare shopping experience is transformative |

||

|

B3 |

I totally believe in inner beauty! |

15 |

|

A1 |

I want perfect skin |

15 |

|

D5 |

I’m a more visual shopper… I love touching, smelling and seeing all the products |

11 |

|

B5 |

I need a make-up that taps into my flirty and sensual side |

10 |

|

Glamorize: My ultimate skincare shopping experience is glamorizing |

||

|

E2 |

I ask a lot of questions to get all the product details… even though I’ve done my own research |

13 |

|

F5 |

When I am purchasing makeup, skincare products or fragrances, I like the staff to be playful, spontaneous and funny |

12 |

|

D1 |

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

11 |

|

B2 |

I always want to look like ME, not a made-up version of me |

11 |

|

E4 |

I am someone who loves to customize make-up in her own unique way |

10 |

The Four Mind-Sets for Beauty Shopping

A key tenet of Mind Genomics is that for any specific, describable experience or topics of thought that can be dimensionalized into aspects, people differ from each other in terms of which of the aspects are important. These differences are not in the people, but rather differences in sets of ideas which ‘travel together.’ A good analogy of this is basic colors. Although there are many colors, underneath the myriad of colors that we perceive are three primary colors, red, yellow, and blue respectively. A similar metaphor applies to the many different aspects of a specific topic, such as the shopping experience. Beneath the many different descriptions of a specific type of shopping experience, such as shopping for beauty items, there exist a limited number of basic groups, so-called ‘mind-sets’ in the language of Mind Genomics.

The metaphor of primaries is meant as just that, a metaphor. Nonetheless, by clustering together people based upon the patterns of what they deem to be important (or here, what describes them), we can identify a limited set of different groups of respondents, differing dramatically in what they feel to be important. We are not interested in fine differences, only in large, dramatic differences.

We identify these clusters, called mind-sets, through a simple statistical procedure, clustering. Each of our 251 respondents generates 35 coefficients about importance, showing the degree to which each of the 35 elements drives the binary response emerging from the scale ‘describes me.’ We want to identify two, three, or at most four or so groups differing dramatically from each other in the patterns of elements which describe them.

Our clustering defines the distance between each pair of respondents, using a simple statistic (1-R), where R is the Pearson correlation coefficient. The Pearson R is a measure of the degree to which two sets of measures, our coefficients, co-vary. When R = 1, then the covariation is perfect. Changes in one person’s coefficients exactly track changes in another person’s coefficient. Their distance is 0 (1-R, 1–1 = 0.) They are identical patterns and belong to the same mind set. In contrast, when R=-1, the covariation is opposite. Increases in the value of one person’s coefficient are matches by the same, albeit opposite change, i.e., decrease in the value of the other person’s coefficient. The distance is 2 (1-R, 1- -1 = 2.). They belong in different mind-sets.

Following the foregoing approach, we cluster our 251 respondents, extracting as few clusters or mind-sets as possible (parsimony), while at the same time ensuring that the clusters or mind-sets are interpretable, i.e., ‘tell a story.’

Table 5 shows the four mind-sets for beauty shopping, emerging from the clustering. When we look at the four emergent mind sets from this study we are struck by several findings:

Table 5. Strongest performing elements for four mind-sets for the shopping experience.

|

Mind Set |

A |

D |

C |

B |

|

Base Size |

79 |

72 |

51 |

49 |

|

Additive Constant |

83 |

67 |

37 |

-20 |

|

Mind Set A – About self confidence |

||||

|

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

9 |

0 |

14 |

22 |

|

Mind Set D – Focused on the product and the expert |

||||

|

I want perfect skin |

-12 |

14 |

20 |

15 |

|

I want a “Go To” consultant who knows me intuitively, and can make my experience more personal each time I return |

-8 |

12 |

-8 |

16 |

|

I ask a lot of questions to get all the product details… even though I’ve done my own research |

-13 |

11 |

-20 |

28 |

|

Mind Set D – No really interested in shopping at all , but wants to be sexy |

||||

|

I have combination skin |

-24 |

-2 |

22 |

10 |

|

I want perfect skin |

-12 |

14 |

20 |

15 |

|

My skin is needy |

-31 |

-8 |

20 |

-5 |

|

My skin is unpredictable, always changing |

-34 |

-4 |

17 |

-1 |

|

For me it’s about staying sexy |

-25 |

1 |

17 |

2 |

|

My style… revealing, sexy, with bare, nude, natural make-up |

-1 |

-15 |

14 |

14 |

|

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

9 |

0 |

14 |

22 |

|

Mind Set B – It’s all about the different aspects of the experience, and not basic interest .. can be very excited with the right message |

||||

|

I want the beauty consultant to use an educational approach, using facts, to support their claims |

-2 |

3 |

-1 |

29 |

|

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is pleasurable |

-2 |

-1 |

-7 |

29 |

|

I ask a lot of questions to get all the product details… even though I’ve done my own research |

-13 |

11 |

-20 |

28 |

|

I am someone who loves to customize make-up in her own unique way |

-15 |

9 |

-7 |

28 |

|

My challenge is finding the perfect skincare product |

-12 |

8 |

-8 |

28 |

|

I totally believe in inner beauty! |

6 |

1 |

8 |

25 |

|

I always want to look like ME, not a made-up version of me |

7 |

0 |

11 |

25 |

|

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is therapeutic |

-5 |

-7 |

-17 |

25 |

|

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is informative |

-4 |

-6 |

-15 |

24 |

|

My ultimate skincare shopping experience is transformative |

-6 |

-10 |

-18 |

24 |

|

I need a make up that taps into my flirty and sensual side |

-4 |

-3 |

1 |

24 |

|

I like products that make me feel confident about myself |

9 |

0 |

14 |

22 |

|

I’m a more visual shopper… I love touching, smelling and seeing all the products |

3 |

3 |

8 |

21 |

|

I believe my face and body are a medium for self-expression |

4 |

-2 |

4 |

20 |

|

I always put make-up on before I go out |

1 |

1 |

2 |

20 |

|

I want the beauty consultant to hold my hand, and show me exactly how to use the products |

-20 |

7 |

-21 |

20 |

|

I like brightness, colors, fragrance, soft music; variety… I only go into beauty stores that exude those qualities |

-18 |

6 |

-17 |

19 |

|

At the beauty counter, at first I’m usually a little bit shy and stay to myself |

-8 |

-23 |

8 |

19 |

|

When I am purchasing makeup, skincare products or fragrances, I like the staff to be playful, spontaneous and funny |

-5 |

3 |

-9 |

19 |

- The mind sets are significantly but not equally sized. There are no two large and two tiny mind-sets, but rather four substantially-sized mind-sets.

- The larger mind-sets (A, D) show high additive constants, meaning that they are basically interested in shopping. The elements add a moderate amount. There are only a few of these elements, of a more focused nature.

- The smaller mind-sets (C, B) show much lower constants, meaning that the respondents in these mind-sets are only moderately or not interested in shopping, unless there are specific elements which describe the experience. Fortunately, there are a fair number of important elements for Mind Set C, and many stronger performing elements for Mind Set B.

- We can give names to the mind-sets, based upon the strongest performing elements, but these mind-sets tend not to be unidimensional, except perhaps Mind Set A.

- The clustering generating fewer numbers of mind-sets (two and three) mind-sets are almost impossible to understand. By the time we get to four mind-sets, the data start to tell to tell a clearer story. That is, the strongest performing elements come from a variety of different topics and questions.

- We could create an even deeper segmentation, with many more segments, but then we are violating the spirit of segmentation by sacrificing parsimony to interpretability and simplicity

Finding these Mind-Sets in the Population

When we began this study, we assumed that the recruitment of women who regularly shop for cosmetics in high-end department stores would generate a reasonably homogeneous group of women in terms of their attitudes towards cosmetics, although varying in age, income, residence, education, and so forth. What emerged as most surprising is the radical differences among the respondents in terms of the kinds of messages to which they responded. There was no simple co-variation between WHO THE RESPONDENTS ARE and TO WHAT THE RESPONDENT REACTS POSITIVELY. That is, the conventional methods of segmentation would say that these respondents would be more similar in their mind-sets than the experiment revealed them to be. Most of the reported literature talked about behavior, but not about specific words [11].

The nature of the mind-sets revealed in this and other Mind Genomics experiments suggest that it will be impossible to assign new people to mind-sets based upon general behavior. The assignment can only be very approximate because each situation comprises aspects unique to it, aspects that could never be captured by any sort of detailed knowledge other than detailed knowledge of the topic alone. In other words, one of the emerging findings of Mind Genomics is that there exist these mind-sets, but the mind-sets are intimately related to the nature of the experience itself, and the language used to describe it, as well, of course, the proclivities of the respondent.

Another way to find these mind-sets in the population works with the very elements, the very language used to establish the mind-sets in the first place. The approach uses the data from the mind-sets, looking for the elements or phrases which best differentiate between two mind-sets, or among three mind-sets.

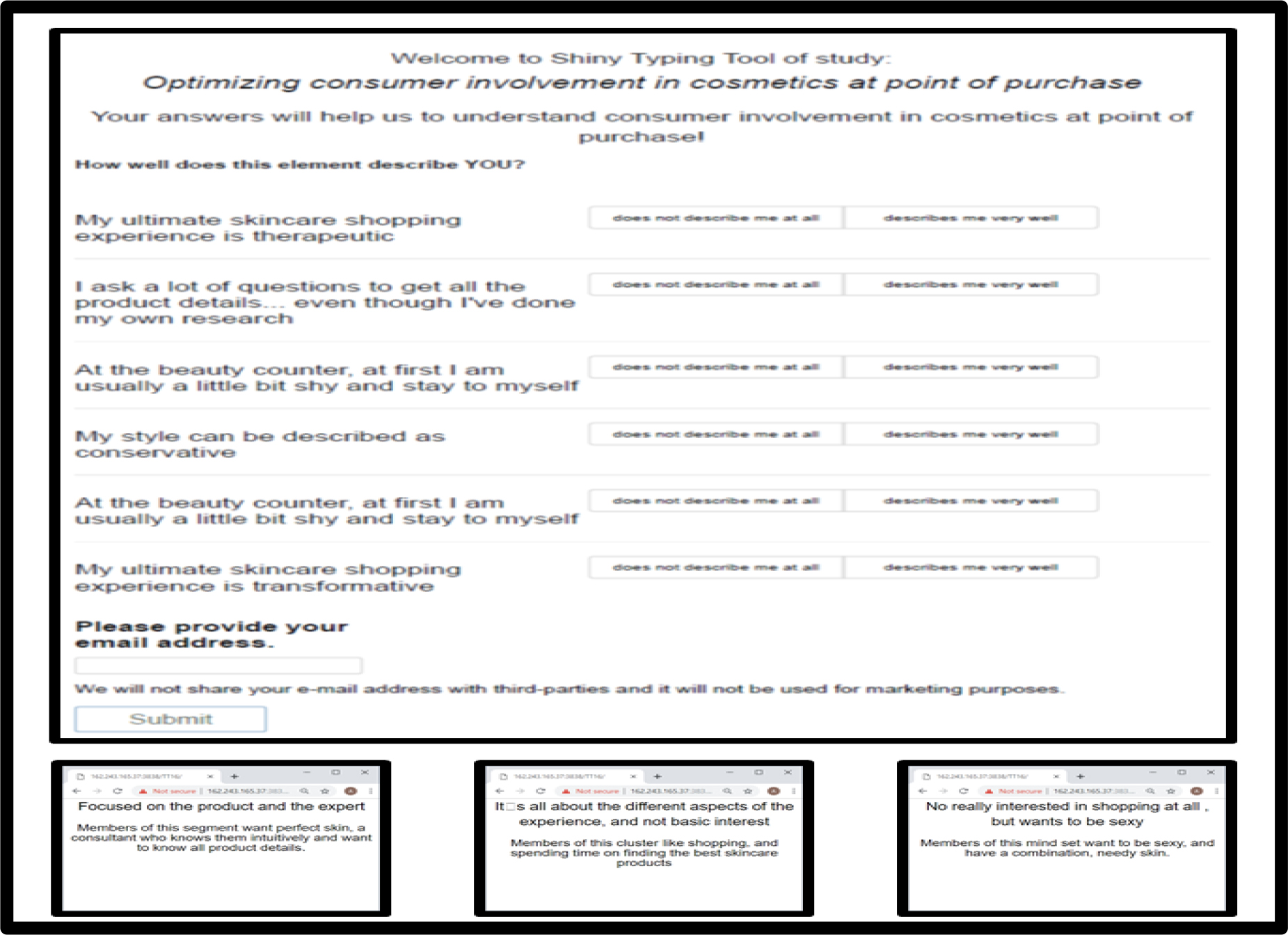

Figure 4, left panel, shows the six question ‘PVI,’ the personal-viewpoint identifier. The patterns of responses to the six questions drive the assignment of the respondent to one of the three mind-sets. In turn, the right panel of Figure 4 shows the of feedback screens emerging when the respondent completes the ratings to the six questions. Each respondent or each salesperson receives the appropriate information. For the respondent the feedback is ‘fun,’ because it’s ‘ABOUT ME.’ For the salesperson the feedback is important because in a very short time the salesperson gets a sense of what to say to this person to improve the likelihood of a positive and productive interaction. In the evolving world of digital commerce, the customer presented with this type of questionnaire, either at the point or earlier, can be ‘tagged’ so that when the customer appears as a shopper, the customer can be sent to the correct website, one particularized to the mind-set. This individualization is NOT based upon the increasingly frowned-upon method of tracking a respondent, but rather asking the respondent to participate in helping the sales process.

Figure 4. The PVI, personal viewpoint identifier, constructed for this particular project. The link to the website as of this writing (2019) is: http://162.243.165.37:3838/TT16/

Discussion and Conclusion

The academic literature in marketing has presented the business community with a variety of methods by which to increase sales. It is now well recognized that the traditional ways of dividing people, by WHO THEY ARE, are insufficient. Methods used to assign respondents to like-minded groups may work better. These groups are so-called psychographic segments. The weakness is that these segments are too general, created from large-scale studies, combined when necessary, with behavioral observation.

There are problems with the traditional methods, problems which are insuperable given the myriad of products and services that one can offer. One insuperable problem is that the psychographic analysis is simply too general, talking about general lifestyles. Even Claritas’ segmentation into more than five dozen segments is not granular enough, as well as defying application in ‘real time’ [12]. The second insuperable problem is that observation is only on behavior, not on thinking. Finally, the most insuperable problem of all, the most important, is that even with successful segmentation through attitudes, lifestyles and behavior, one rarely knows the PRECISE WORDS which appeal to a given individual for a given issue at a given moment. Mind Genomics, whether applied to things or experiences, or even ideas such as ‘justice’ and ‘ethics’ holds the promise of providing that actionable, database insight which can also become the raw material for a new science of the mind [13,14].

Acknowledgment

Attila Gere thanks the support of the Premium Postdoctoral Researcher Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- Green PE, Rao VR (1971) Conjoint measurement for quantifying judgmental data. Journal of marketing research 8: 355–363.

- Green PE, Srinivasan V (1990) Conjoint analysis in marketing: new developments with implications for research and practice. The journal of marketing 54: 3–19.

- Anderson NH (1981) Information integration theory. Academic Press.

- Gere A, Shelke K, Batalvi B, Zemel R, Sciacca A, et al. (2019) Messaging Food and Inner Beauty Together… an Experiment in Cognitive Economics 2: 1–14.

- Gere A, Zemel R, Papajorgji P, Sciacca A, Kaminskaia J, et al. (2018) Customer Requirements for Natural Food Stores – The Mind of the Shopper. Nutrition Research and Food Science Journal 1: 1–12.

- Zemel R, Gere A, Papajorgji P, Zemel G, Moskowitz HR (2018) Uncovering Consumer Mindsets Regarding Raw Beverages, Food and Nutrition Sciences Pub. Date: March 30, 2018.

- Gabay G, Zemel G, Gere A, Zemel R, Papajorgji P, et al. (2018) On the Threshold: What Concerns Healthy People about the Prospect of Cancer? Cancer Studies and Therapeutics Journal 3: 1–10.

- Kahneman D, Egan P (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Leardi R (2009) Experimental design in chemistry: A tutorial. Anal Chim Acta 652: 161–172. [crossref]

- Moskowitz H, Gofman A (2003) I novation Inc, 2003. System and method for content optimization. U.S. Patent 6,662,215.

- Yousaf U, Zulfiqar R, Aslam M, Altaf M (2012) Studying brand loyalty in the cosmetics fforum. http:STUDYING BRAND LOYALTY IN THE COSMETICS INDUSTRY. LogForum, 8(4).

- Weinstein A, Cahill DJ (2014) Lifestyle market segmentation. Routledge.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling blue elephants: How to make great products that people want before they even know they want them. Pearson Education.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of sensory studies 21: 266–307.